Chewing mouthparts in insects are adapted for biting and grinding solid food, commonly found in beetles and grasshoppers, enabling them to consume leaves and other plant material. Piercing-sucking mouthparts, characteristic of aphids and mosquitoes, allow insects to puncture plant or animal tissues and extract fluids like sap or blood. These structural differences reflect specialized feeding strategies essential for insect survival and ecological interactions.

Table of Comparison

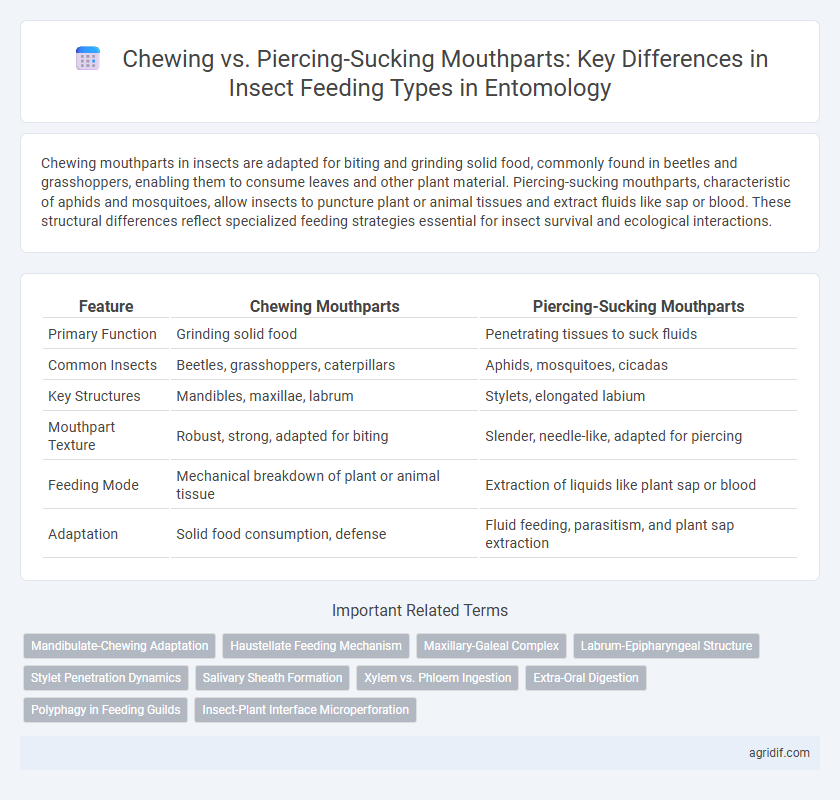

| Feature | Chewing Mouthparts | Piercing-Sucking Mouthparts |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Grinding solid food | Penetrating tissues to suck fluids |

| Common Insects | Beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars | Aphids, mosquitoes, cicadas |

| Key Structures | Mandibles, maxillae, labrum | Stylets, elongated labium |

| Mouthpart Texture | Robust, strong, adapted for biting | Slender, needle-like, adapted for piercing |

| Feeding Mode | Mechanical breakdown of plant or animal tissue | Extraction of liquids like plant sap or blood |

| Adaptation | Solid food consumption, defense | Fluid feeding, parasitism, and plant sap extraction |

Overview of Insect Feeding Types

Chewing mouthparts are characterized by strong mandibles that allow insects to bite and grind solid food, typical in beetles and grasshoppers. Piercing-sucking mouthparts consist of elongated stylets designed to penetrate tissues and extract fluids, common in mosquitoes and aphids. These distinct feeding adaptations reflect evolutionary specialization in insect dietary habits and ecological roles.

Structural Differences in Mouthparts

Chewing mouthparts in insects feature robust mandibles and maxillae designed for biting, cutting, and grinding solid food, supported by a labrum and labium that provide stability and manipulation during feeding. Piercing-sucking mouthparts, characteristic of Hemiptera, consist of elongated, needle-like stylets formed by modified mandibles and maxillae enclosed within a flexible labium sheath, enabling the insect to penetrate host tissue and extract fluids. Structural specialization in these mouthparts reflects adaptations to distinct feeding strategies, with chewing types optimized for mechanical breakdown and piercing-sucking types for fluid ingestion.

Chewing Mouthparts: Morphology and Function

Chewing mouthparts in insects consist of mandibles, maxillae, and labium adapted for biting and grinding solid food, primarily plant material or prey. Mandibles are robust, sclerotized structures that enable mechanical breakdown of food, while maxillae assist in manipulating and tasting food items. This morphology supports herbivorous and predatory feeding behaviors, allowing efficient ingestion of diverse solid diets.

Piercing-Sucking Mouthparts: Adaptations and Design

Piercing-sucking mouthparts in insects, such as those found in Hemiptera and mosquitoes, are specialized for penetrating host tissues to access liquid food sources, primarily plant sap or animal blood. These mouthparts consist of elongated stylets formed from modified mandibles and maxillae, encased within a protective labium that acts as a sheath during feeding. Adaptations include sensory structures for host detection and anticoagulant saliva to maintain fluid flow, optimizing efficient nutrient extraction and minimizing host damage.

Major Insect Orders with Chewing Mouthparts

Major insect orders with chewing mouthparts include Coleoptera (beetles), Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets), and Blattodea (cockroaches). These insects possess mandibles designed for biting and grinding solid food, enabling them to feed on a wide range of plant and animal materials. Chewing mouthparts contrast with piercing-sucking types found in Hemiptera, specialized for extracting fluids.

Major Insect Orders with Piercing-Sucking Mouthparts

Major insect orders with piercing-sucking mouthparts include Hemiptera, such as aphids and cicadas, renowned for extracting plant sap or animal fluids efficiently through their specialized stylets. Thysanoptera, or thrips, utilize piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on plant cells, causing significant agricultural damage. Another notable group is the order Diptera, specifically mosquitoes, which employ these mouthparts to pierce host skin and withdraw blood, facilitating disease transmission.

Impact on Crop Damage and Symptoms

Chewing mouthparts, found in insects like beetles and caterpillars, cause significant physical damage to crops by consuming leaves, stems, and fruits, leading to visible holes, defoliation, and reduced photosynthesis. In contrast, piercing-sucking mouthparts, characteristic of aphids, whiteflies, and leafhoppers, inflict damage by extracting plant sap, resulting in chlorosis, wilting, and transmission of plant pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. The type of mouthpart directly influences the nature and severity of crop damage, impacting yield quality and necessitating targeted pest management strategies.

Feeding Behavior and Plant Interactions

Chewing mouthparts, found in insects like beetles and caterpillars, enable the mechanical breakdown of plant tissues, causing visible damage such as holes and leaf edge feeding that influence plant growth and defense responses. Piercing-sucking mouthparts, characteristic of aphids and leafhoppers, allow insects to extract plant sap by penetrating vascular tissues, which can result in nutrient depletion and transmission of plant pathogens. These distinct feeding behaviors drive different plant-insect interactions, with chewing insects often triggering structural defenses, while piercing-sucking insects impact plant physiology and systemic responses.

Pest Management Implications

Chewing mouthparts enable insects to consume solid plant material, causing extensive foliar damage that necessitates targeted pest control strategies such as insecticidal applications and mechanical removal. Piercing-sucking mouthparts allow insects to extract plant sap or bodily fluids, often transmitting plant pathogens and requiring systemic insecticides or biological control agents for effective management. Understanding the specific feeding mechanisms aids in developing integrated pest management approaches tailored to disrupt feeding behavior and minimize crop losses.

Evolutionary Significance of Mouthpart Diversity

Chewing mouthparts, characterized by mandibles for biting and grinding, represent a primitive feeding adaptation that supports herbivory, predation, and detritivory, facilitating the exploitation of diverse food sources. Piercing-sucking mouthparts, evolved independently in multiple insect orders such as Hemiptera and Diptera, allow the extraction of liquid nutrients from plants, animals, or other insects, reflecting a specialized evolutionary strategy for feeding efficiency and niche differentiation. The evolutionary diversification of mouthparts underscores adaptive radiation in insects, enhancing survival by enabling exploitation of varied ecological niches and minimizing interspecific competition.

Related Important Terms

Mandibulate-Chewing Adaptation

Mandibulate-chewing mouthparts, characterized by robust mandibles, enable insects such as beetles and grasshoppers to mechanically break down solid plant or animal tissues, enhancing their ability to process diverse diets. This adaptation contrasts with piercing-sucking mouthparts found in Hemiptera, which are specialized for extracting liquid nutrients through slender stylets, reflecting distinct evolutionary feeding strategies within insect taxa.

Haustellate Feeding Mechanism

Haustellate feeding mechanisms in insects involve specialized mouthparts adapted for piercing and sucking, enabling efficient extraction of plant sap or animal fluids, as seen in Hemiptera and mosquitoes. In contrast, chewing mouthparts, typical of beetles and grasshoppers, consist of mandibles designed to bite and grind solid food, reflecting distinct evolutionary adaptations for diverse dietary sources.

Maxillary-Galeal Complex

The maxillary-galeal complex in insects with chewing mouthparts consists of robust, sclerotized structures adapted for grinding and manipulating solid food, while in piercing-sucking mouthparts, this complex forms slender, needle-like stylets specialized for penetrating plant or animal tissues to extract fluids. Morphological adaptations in the maxillary and galeal components directly influence feeding efficiency and specialization within diverse insect taxa, such as Coleoptera (chewing) and Hemiptera (piercing-sucking).

Labrum-Epipharyngeal Structure

The labrum-epipharyngeal complex in insects with chewing mouthparts functions as a robust, movable upper lip that aids in mechanical food breakdown, whereas in piercing-sucking mouthparts, this structure is often modified into a slender, stylet-like apparatus facilitating penetration and fluid extraction. Morphological adaptations of the labrum-epipharyngeal region reflect the insect's feeding strategy by either supporting mastication or enabling precise host tissue puncturing and sap ingestion.

Stylet Penetration Dynamics

Chewing mouthparts, characterized by mandibulate structures, mechanically break down solid food, while piercing-sucking mouthparts utilize slender stylets to penetrate plant or animal tissues, enabling fluid extraction. Stylet penetration dynamics involve precise muscle control and enzymatic saliva release to facilitate tissue penetration and optimize nutrient uptake without triggering host defenses.

Salivary Sheath Formation

Chewing mouthparts in insects, such as beetles and grasshoppers, mechanically break down plant or animal tissues, producing solid food particles for ingestion without forming a salivary sheath. Piercing-sucking mouthparts, found in hemipterans like aphids and mosquitoes, inject saliva that solidifies into a protective salivary sheath enveloping the stylets, facilitating efficient fluid extraction and preventing tissue damage.

Xylem vs. Phloem Ingestion

Chewing mouthparts enable insects like beetles to mechanically break down plant tissues, consuming a variety of solid materials, whereas piercing-sucking mouthparts, found in aphids and cicadas, are specialized for accessing plant vascular fluids. Insects with piercing-sucking mouthparts selectively ingest xylem or phloem sap, where xylem feeders extract water and minerals under tension while phloem feeders consume nutrient-rich sugars and amino acids critical for their development.

Extra-Oral Digestion

Chewing mouthparts mechanically break down solid plant material or prey, facilitating ingestion, whereas piercing-sucking mouthparts inject digestive enzymes into host tissue to initiate extra-oral digestion before fluid extraction. This enzymatic breakdown outside the body allows insects such as aphids and assassin bugs to efficiently consume liquid nutrients while bypassing physical digestion.

Polyphagy in Feeding Guilds

Chewing mouthparts enable polyphagous insects to consume a wide variety of plant tissues, facilitating diverse feeding strategies within entomological guilds. In contrast, piercing-sucking mouthparts allow polyphagous insects to access liquid nutrients from multiple host plants, enhancing their adaptability across various ecological niches.

Insect-Plant Interface Microperforation

Chewing mouthparts, characterized by robust mandibles, physically break down plant tissues, creating larger wounds that facilitate nutrient access but increase plant vulnerability to herbivory and pathogen entry. Piercing-sucking mouthparts penetrate plant cells via microperforations, enabling insects to extract sap efficiently while minimizing tissue damage and reducing the plant's defensive response, thus representing a specialized adaptation at the insect-plant interface.

Chewing mouthparts vs piercing-sucking mouthparts for insect feeding types Infographic

agridif.com

agridif.com